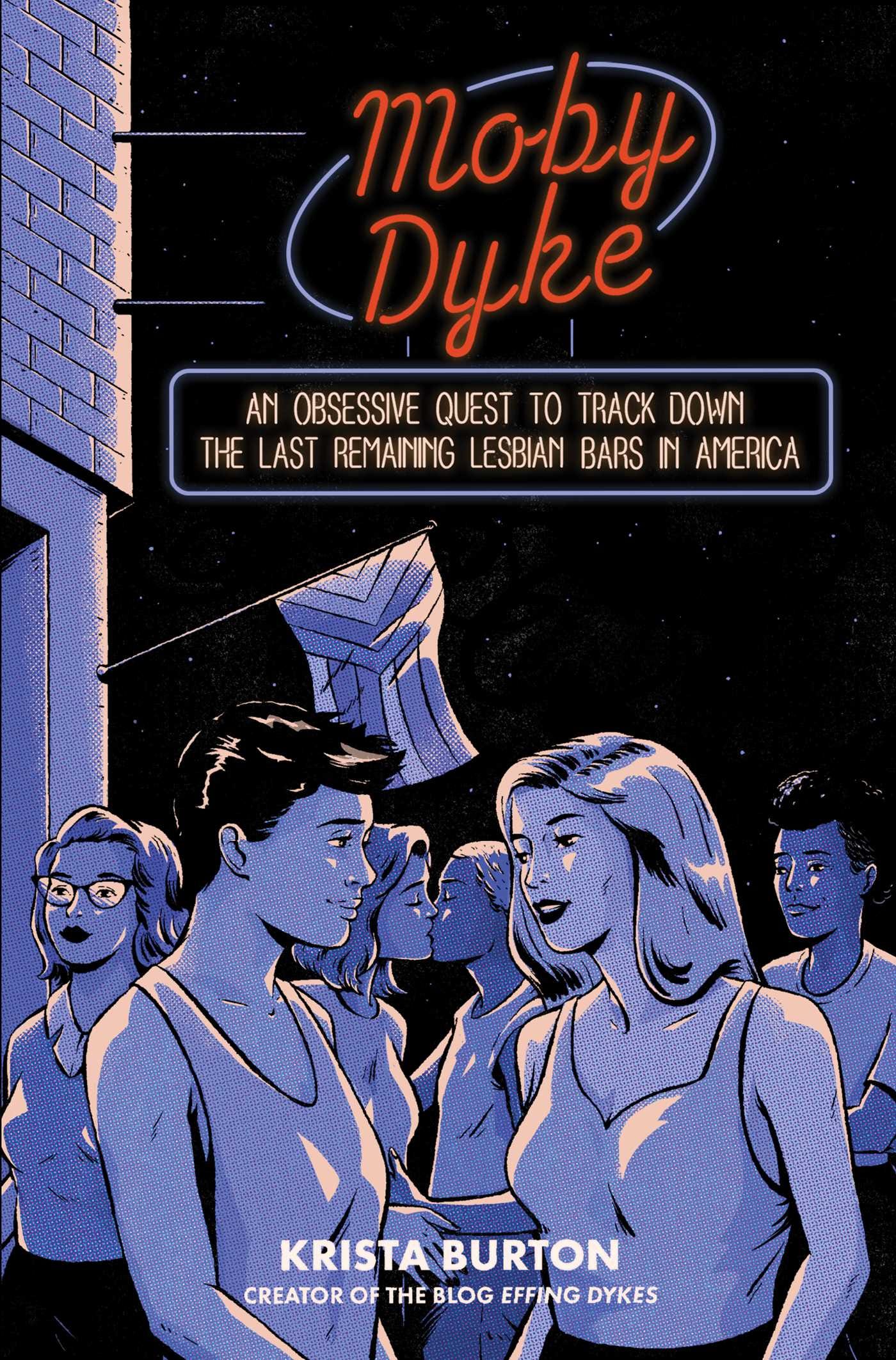

You shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, except you can and I do, which is how I ended up with a hardcover copy of Moby Dyke in my collection.

While the inside cover told me I’d be exploring questions like why are lesbian bars vanishing? What does it mean to be a lesbian bar? Who is welcome in lesbian bars? What do these bars offer queer communities that can’t be found elsewhere? in the first 107 pages these questions seem like they’ve been all but abandoned.

I came out as bisexual in college, mainly inspired through a mix of seeing more and more posts about being queer on tumblr and sharing those posts with my college friends, as we all came into our queer identities on our own timelines. Outside of my small circle of college friends and my sister, my queer community was largely a virtual one. I made friends with queer writers through fandom, and considered my queer community fairly expansive if not geographically convenient to me.

The experience of going to lesbian bars and finding community in them wasn’t mine, but it was something I have had an odd hunger for. Odd because I’ve never been much for going to bars, and I’m only a social drinker on occasion. And, no matter how many times I bemoan how the little dive in our neighborhood used to be a lesbian bar1, I know deep down it’s probably a lie when I say I’d go there if it still was.

But, the longing for a queer community so full and near that you could literally reach out and touch it was one that resonated with me–possibly because of how much I have depended on virtual communities. And the numbers are shocking: there used to be 206 lesbian bars in America, as recently as 1987? Now there’s only twenty? How can that be happening in a world that claims to be more accepting of queer people?

I wanted to know and Burton promised to explore it with me.

But I’ve been queer theory baited2 because Moby Dyke isn’t actually concerned with any of these questions. It’s not really about queer spaces at all. While it claims, (or, maybe more generously, hopes) to be a treatise on queer spaces and lesbian culture, Moby Dyke is too concerned with proving Burton’s claim to queer spaces to be either of those things.

Other than Burton herself, while reading it I couldn’t figure out who this book was written for. It’s a subject queer people care about, but it never felt like I, as a queer reader, was being spoken to. Only spoken about in broad generalizations. As I read I kept encountering moments where touch points of queer American culture were suddenly being explained to me in easy, simplistic terms. As though the reader who picked up a book with Dyke in the title had never heard of Stonewall:

“The Stonewall Inn is both a gay bar and the birthplace of the modern gay rights movement. That’s because on June 28, 1969, the bar was raided by the police and…the patrons fought back. Hard.

… Shit hit the fan. As the night went on, the crowd outside The Stonewall Inn grew bigger and angrier. People started rioting: more police arrived. By the next night, the news about the riots at Stonewall had spread, and thousands of people gathered on Christopher Street, smashing shit, lighting fires in trash bins, and throwing things at the hundred new cops who’d been sent to contain the riots. The night after that, thousands more people were there, fighting a street battle against the police, which they won. That’s how Pride began. The first Pride was a riot. (And that’s why there’s a constant fight about whether or not cops should be allowed at Pride: because Pride began with queer people finally pushing back against the enforcers of systematic oppression, the cops who had pushed them around so many years.”

Moby Dyke, p. 54-55

It’s not that the account is inaccurate, but reading it feels a little like jumping back in time to the 2010s tumblr buckle up kiddos I’m about to learn you a thing era. It’s casual and sanitized and feels–and I’m sorry for sounding dramatic here–disrespectful to the history that The Stonewall Inn represents to simplify the event this way.

Yes, she makes note of “bullshit laws concerning gay people” but what was it like to live under those laws daily? What does it actually mean for your existence to be a crime? What did those laws mean for queer people, outside of the context of queer bars? What danger and violence did the people rioting face if they were arrested? How were queer and trans folks already regularly being abused by law enforcement? All of these questions inform why the rioting at Stonewall happened.

Queer bars were raided frequently and the people at Stonewall fought back but it wasn’t just about access to queer bars. It was about every other social and legal factor that made gay bars some of the only places queer people could gather in “public” authentically and joyfully–and with as much safety as could ever be guaranteed. It was about the dehumanization that came with seeing that one place raided and destroyed, and the violence that came as punishment for existing not just there, but everywhere. It was about the ways in which there is no safe way to be marginalized, because law enforcement and the ruling class will always make your existence a crime.

That’s why Pride is anti-police–not just because the first Pride was a riot against the police, but because being gay and trans was a crime. The violence at the Stonewall Inn was just one moment of survival through resistance.

Compare it to how Leslie Feinberg describes bar set police violence against queer patrons in Stone Butch Blues:

She was interrupted by a hand on her shoulder that spun her around. I was pushed hard from behind. When I turned I caught a glimpse of a cop car with both doors open. The two cops were pushing us with their nightsticks. “Up against the wall, girls.” They pushed us into an alley. Ed put her hand on the back of my shoulder as reassurance.

“Keep your hands to yourself, bulldagger,” one cop yelled as he slammed her against the wall.

[…] One of the cops grabbed a handful of my hair and jerked my head backward as he kicked my legs apart with his boot. He took my wallet out of my back pocket and opened it.

[…] The other cop began shouting at Ed. “You think you’re a guy, huh? You think you can take it like a guy? We’ll see. What’s these?” he said. He yanked up her shirt and pulled her binder down around her waist. He grabbed her breasts so hard she gasped.

“Leave her alone,” I yelled.

“Shut up you fuckin’ pervert,” the cop behind me shouted and bashed my face against the wall. I saw a kaleidescope of colors.

[…] There are times, the old bulls told me, when it’s best to take your beating and hope the cops will leave you on the ground when they’re done with you. Other times your life may be in danger, or your sanity, and it’s worth it fight back. It’s a tough call.

Stone Butch Blues, p. 66-67

It’s a fictional account, but it’s also raw and honest and no doubt informed by Leslie Feinberg’s lived experience as a butch dyke. This is what Burton all too gently alludes to when she says the police “pushed them around for so many years.”

The queer joy found in these spaces can’t be separated from the bravery that came along with simply entering them. It’s not given the weight it deserves in Moby Dyke, where we’re suddenly in a world, similar but parallel to ours, where queer people have been ubiquitously accepted and embraced everywhere and the only struggle left for our community is to combat internal femmephobia3.

“Femmes, who often look more traditionally feminine, are not recognized or celebrated in the same way as masc-presenting queers.”

Moby Dyke, p. 96

On tumblr, which was where I found my online queer community, there’s a feeling of queer people finally having space to come together with other people like them to express themselves in ways that challenge the cultural norm. Queer women can post about not wearing makeup, not shaving their legs, and living in defiant opposition to the male gaze where women are only allowed to be one specific image–and can find women who experience gender just like them.

This seeming popularity of gender non-conformity can start to feel universal within the smaller community you’re in, and you can forget that just outside this space dominant culture rewards you (with safety, wealth, access, etc.) for how you present.

Defining femmephobia in this way–as the marginalization of femininely presenting women–is a manifestation of both this phenomenon and choice feminism, where every choice a woman makes is seen as liberatory because she made it, regardless of the social and cultural context that informed the choice.

Passing is painful. As a non binary person, I’ve accepted that the majority of strangers who see me on the street will assume I’m a woman. I’m not, and I wish the culture we lived in didn’t assume anyone’s gender based on looks–but I also know, and cannot ignore how this decreases my risk of being a victim of transphobic violence while simply existing in public.

This exchange–misunderstanding for safety–is not one Burton is willing to interrogate at all in Moby Dyke. Instead, there’s no exploration of what passing means outside of the context of dyke bars–or how that could contribute to her ability to travel across the country indiscriminately to visit the very places she writes about.

“I was psyching myself out. I really liked Walker’s Pint, but I was five bars into visiting all the lesbian bars in America, and I was already getting a little wary. In the bars I’d been to so far, most queers were friendly and didn’t mind being approached, but some had been lightly or openly hostile to me, a strange person who they likely perceived as straight, coming up to them in one of the only spaces they could call their own. Which I absolutely get!! It’s just that: I’m also gay, and sometimes this shit hurts my feelings.”

Moby Dyke, p. 99

Attributing all wariness in other patrons to femmephobia is a repeated myopic thread that ignores obvious alternatives. Maybe in a country that is stripping away rights of LGBTQ folks, wariness of someone new coming into your space with a notebook and a lot of questions is frightening. Maybe it’s not about whether Burton is read as queer or straight at all, and more about the fact that being queer isn’t an all access pass to every group of queer people encountered, and that in marginalized communities, trust in strangers isn’t a luxury frequently indulged in.

Consider Burton’s perspective on the importance of dyke bars as queer spaces:

These bars provided the queers who went to them with several things:

Confirmation that there were others like them

Potential lovers and friends

A tight-knit community/queer family/network

The only spot in town where they could be openly affectionate with other queer people (assuming the bar was safe on a given night)

There’s a glaring omission in this list: these bars were also the only public spaces butch and gender non conforming lesbians could dress in alignment with their gender expression.

Feeling the threat of transphobic or homophobic violence, now, in this world that claims it doesn’t need dyke bars, is a fraction of the fear dykes of older generations would feel when the law required them to wear no less than three pieces of “women’s” clothing or risk arrest. Being able to have a space where GNC dykes could show up with their authentic presentation isn’t just about gender equality, but queer gender affirmation.

Disappointingly, the only conversation Moby Dyke engages in with regards to gender, completely erases this context. I’d be interested to hear what Burton’s husband Davin, a trans man, experiences when she experiences what she defines as femmephobia.

The gender politics of Moby Dyke are messy at best, and disorientingly contradictory at times. At one moment Burton explains her lesbian identity was not changed, merely expanded by her attraction to her husband (p. 47) and yet when proposing Davin accompany her on her visits, Burton defines Davin’s claim to the space through his connection to herself:

“Do you want to come?” I asked. “On the bar trips?”

He looked up. “No.” A pause. “I mean, yeah, but no. This is a book about lesbian bars.”

“Yeah, and you’ve been hanging out in lesbian bars your whole life.4”

“I’d feel weird. This is your book. And it’s about lesbian spaces. I don’t want to take up space that isn’t meant for me.”

“I’m a lesbian, and I’m also married to a trans man,” I said, annoyed. “These bars are for you, too.”

Moby Dyke, p. 13

If I was generous, I’d applaud Burton for her honesty in admitting her annoyance. As a non binary dyke, my own irritation flared up reading that. I’ve often wondered: how would I be received in a queer spaces not centered around women? Would I be welcome? Would the idea that all are welcome hold up if and when my gender starts to make people uncomfortable? Or, like Davin, would I need someone on my arm as a ticket in? Is it truly my space to exist in, or only by proxy, as Burton is characterizing it?

“I didn’t know it at the time of my conversation with Lisa, but her exact statement of welcoming everybody would become such a theme on these trips that we should probably make a drinking game out of it. Take a shot anytime someone says a variation of ‘We’re a lesbian bar but everyone’s welcome,” folks at home who drink!

…most of us also want each and every version of queerness to be welcome in those spaces, and who gets to decide who’s queer and who’s not? Who gets to take up space in our bars, the only dedicated spaces we have left? It’s a bit like Pride–yes, we’re all thrilled that being queer is so much more acceptable to society, and also, my god there are so many straight people and corporations at Pride, the only large scale event by, for and celebrating queers, that a lot of queers no longer even go to it.”

Moby Dyke, p. 42-44

We all know the stereotype of gay men’s bars being overrun by cis women’s bachelorette parties, but I’d never really heard the same about lesbian bars. And while Pride is definitely a commercialized shadow of what it once was, I have to note that if Burton and her husband would be seen as straight (by her own definition) in these spaces, isn’t it possible that other’s who are being read as cis or straight are also queer and passing?

Maybe an additional question to ask when getting curious about why lesbian bars are shifting and evolving is: why is there such binary reinforcement of gender and sexuality, even within queer spaces?

Historically, the word lesbian referred to a resident of the Isle of Lesbos–the most famous of which is the poet Sappho, who is famous for her romantic, erotic verses about and relationships with women. From this, the word lesbian came to mean “woman attracted to other women,” but Sappho herself was what we’d now refer to as bisexual, having relationships with men and women alike. In this sense, is the widening of the definition of what a lesbian space is to center women attracted to other women, but not exclude varying and related identities, honoring the historical meaning of the word? This is not a question Burton explores.

At so many different points through just the first third of Moby Dyke, Burton speaks with an unrecognized universality that can only exist when you see yourself as the default. She refers to queer/lesbian/dyke culture as a monolith as though race, class, gender and sexuality play no part in creating and defining the lived experiences within those cultures. Burton isolates lesbian culture from political and historical context completely, tossing out any chance for a deeper understanding of these spaces, what they mean, and what they provide–for queer and straight readers alike.

Maybe if I made it further, I’d find more satisfactory answers to the questions posed. Maybe I’d get to dig into questions like: if lesbians are becoming so much more accepted in our culture, why is no one patronizing their businesses? Wouldn’t more people be seeking out these spaces, making them more popular if queer people are truly being more welcomed into the dominant culture? Why have so many more gay men’s bars survived? Maybe Burton herself would have dug into the need to label everyone around her as various types of hyper-specific queer people, to realize she could no more accurately understand someone’s identity by looking at them than someone could know the intricacies of her queerness by looking at her. Or maybe not.

If you want to support our work you can send us a tip here:

The questions this book promised got me curious about why my neighborhood dyke bar was a thing of the past; with a few minutes of Googling, I was able to find a video interview with the previous owners in a collection on the public library website! Turns out: it was just a lot of work, it was their second business together, and after years of running it they felt it was time to call it quits.

I know, I read the introduction. She promised a non-academic book. But these questions require thought, nuance, and work to answer. Curiosity doesn’t require an academic background.

When I first encountered the term femmephobia, I thought it referred to a particular manifestation of homophobia, where femme queer men are punished for their gender expression, or perhaps commentary on the way in which femme queer women express their gender in a fashion outside and distinct from the male gaze, and the social repurcussions that comes with it. Unfortunately within the context of Moby Dyke, it’s a thinly veiled method of perpetuating butchphobia.

An experience that would have added a depth to the book had it been explored! Unfortunately, in the 100+ pages I got through, it wasn’t touched on again.